Are Trade Wars Really Just Class Wars in Disguise?

This is the second in a two-part series about economic constraints on household thrift and the inevitable failure of financial education.

Last week, we argued against the dominant narrative that low household savings and poor retirement outcomes are due to individual deficits in financial education or personal thrift. In doing so, we introduced the “Paradox of Thrift,” explaining how widespread aggressive savings can harm the economy by reducing aggregate demand. We also discussed how asset price inflation disproportionately benefits the wealthy and diminishes future returns for new savers, and how labor market stagnation, driven by corporate financialization, further hinders financial independence.

In this post, we’ll demonstrate that US household savings are not a choice made by individuals, but an endogenous variable dependent on larger structural economic forces. To begin, let’s take a look at personal savings rates across a swath of different countries:

| Country | Personal Savings (% of GDP) |

|---|---|

| South Korea | 35.6% |

| Sweden | 25.4% |

| China1 | 23.0% |

| Germany | 11.3% |

| Japan | 5.0% |

| United States | 4.8% |

| Australia | 0.6% |

| South Africa | -1.1% |

So, why do countries like South Korea, Sweden and China have higher household savings rates than the United States? It would be easy to assume that Koreans and Swedes are naturally thriftier or that their culture prioritizes financial education and prudent savings. On the other hand, spendthrifts like Japan, the United States, Australian and South Africa must be deficient in delaying gratification or financial savvy. If we could only teach those South Africans how South Korea does it, right?

Unfortunately the financial literacy crowd confuses cause and effect, ignoring macroeconomic factors like global trade imbalances that too often dictate domestic savings rates. To understand why individual thrift is ineffective against macroeconomic constraints, we must acknowledge a fundamental open-economy macroeconomic accounting identity. This identity establishes that a country’s current account balance (C A)2, which is largely determined by the trade balance, exports (X) minus imports (M), must equal the difference between its national savings (S) and its domestic investment (I):

C A = S − I = X – M

National savings (S) comprises both private savings (household and business) and public savings (the government budget balance: taxes minus spending, T – G).

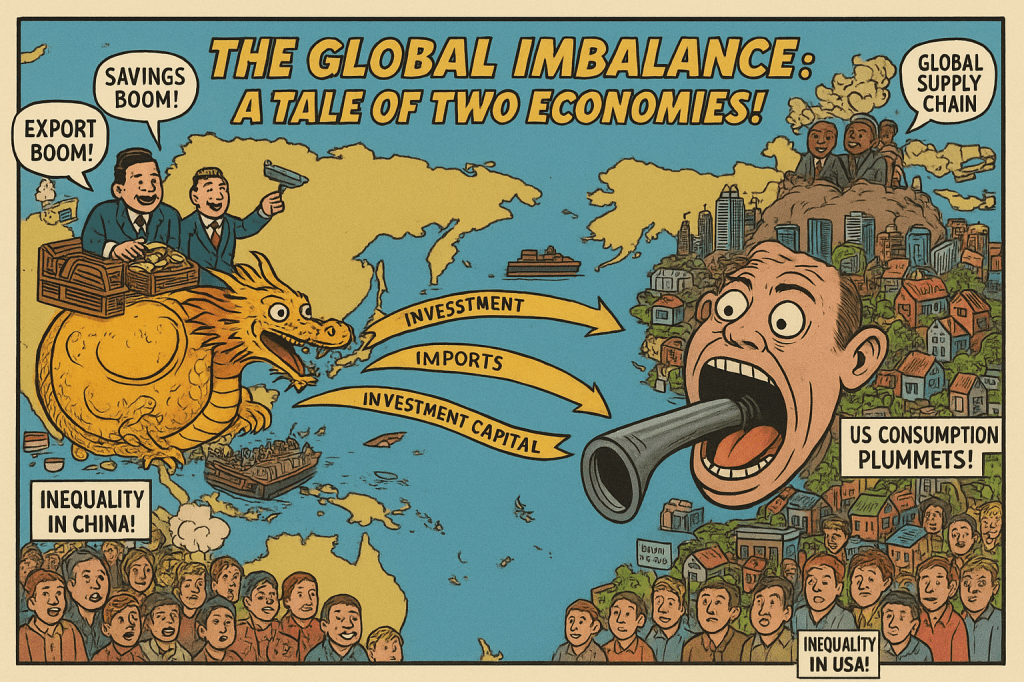

Countries with large and persistent current account surpluses (C A > 0) by definition export more than they import, and save more than they invest domestically. The United States on the other hand has consistently run a large and persistent current account deficit (C A < 0). The flow of capital therefore is from surplus countries like China into deficit countries like the United States.

Mainstream economists suggest that the US trade deficit is the result of insufficient savings (both personal and business) and large government budget deficits. But the story is more complicated than that. As Michael Pettis (professor of finance at at Peking University in Beijing) explains, there is a second explanation that suggests such imbalances originate abroad:

The thinking goes that the United States accommodates these imbalances, partly because it has very deep, liquid capital markets with highly credible governance, and partly because of its role as the capital shock absorber of the world. According to this explanation, surplus countries—usually, I might add, because of policies that suppress domestic consumption—have savings that exceed their domestic investment needs and must export these excess savings abroad to run trade surpluses and avoid unemployment. These surplus countries prefer to export a substantial portion of their excess savings to the United States and, as they do so, they push down the cost of capital.

This is a capital-dominant explanation that doesn’t leave much room for personal behavior. Pettis seems more partial to this explanation than the other and explains it in detail in a blog post at The Carnegie Endowment3.

Either way, individual household savings are merely one component of S in the formula above. If global trade requires the national savings rate to be low to sustain the current global balance, then any significant, widespread increase in individual savings will be offset by adjustments elsewhere in the identity (such as through business dissavings or increased government debt), which would likely be undesirable. Structural policy, therefore, imposes a limit on the aggregate outcome of individual thrift.

Trade Imbalance as Demand Export and Industrial Erosion

Countries that run persistent current account surpluses (China being the most prominent example) do so by subsidizing manufacturing at the expense of domestic consumption, effectively forcing up the domestic savings rate. Again, Pettis provides some examples of policies on his blog along with their affect on consumers:

| Trade Subsidy | Effect on Consumers |

|---|---|

| Undervalued Currencies | Imports become more expensive, making consumption more expensive. This causes a real reduction in the household income share of GDP. |

| Repressed Interest Rates | In economies in which households are largely net lenders, repressed interest rates force households to subsidize credit costs. |

| Overspending or Inefficient Spending on Transportation and Infrastructure | The economic losses associated with overspending on nonproductive infrastructure are allocated across the economy, including to households. |

| Centrally Directed Credit | Credit risks are absorbed indirectly by households through low deposits rates. |

| Low Penalties for Environmental Degradation | Environmental degradation raises health and absentee costs for workers and households. |

| Repressive Labor Laws | Repressive laws reduce labor power, making it harder to keep wage growth in line with productivity growth. |

| Worker Mobility Restrictions (for example, China’s Hukou System) | Restrictions increase costs for migrant workers by depriving them of local social benefits. |

In China, the current account surplus is sustained by high corporate savings and maintaining domestic consumption as a small share of GDP. These distortions create systemic income inequality within China and artificially lowers the cost of credit for enterprises with financial access, effectively subsidizing corporate investment. This subsidy is financed by the savings of relatively poorer individuals who deposit their funds but are unable to borrow. China’s high savings rate (and their current account surplus) are therefore the direct result of policies that favor manufacturers over households.

The persistent US current account deficit, on the other hand, is the necessary mirror image of global capital flows. Countries that run trade surpluses (where exports exceed imports) must, by identity, have national savings exceeding domestic investment. These countries, such as China, effectively “export” consumer demand abroad by selling more goods than they consume domestically, lending their excess savings to deficit countries like the US.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

If these findings are to be believed, aggregate saving rates are driven primarily by macroeconomic policy, not individual thrift or financial education. The structural savings deficit in the US is inextricably linked to the structural savings surplus in countries like China. The immense external imbalance between the US and China is rooted in economic and industrial policies that distort consumption and savings. Low household savings will likely continue to persist so long as this dynamic exists.

So what can policymakers do to address these imbalances? Readers might assume that Pettis is engaging in China-bashing or apologizing for the current administration’s China policies. On the contrary, Pettis lives in China. Furthermore, he believes that tariffs are a blunt instrument and their effects will probably be limited or even counterproductive.

Alternatively, mirroring China’s policies in an attempt to increase the household savings rate could have devastating consequences for those at the lower end of the income range—eroding their purchasing power and transferring income to the government or the manufacturing sector. This would be a race to the bottom at the expense of workers.

Instead, Pettis argues for a multilateral approach, preferably, and failing that, a unilateral approach. The multilateral approach would involve broad trade and capital agreements among a coalition of international allies, which would likely include the introduction of a new world currency. John Maynard Keynes proposed such a solution (the bancor) after World War II.

The unilateral approach would consist of a form of capital controls—in this case limiting the flow of capital into the United States. If the problem lies with capital flows, limiting the inflow of capital from abroad could address the imbalance if enacted intelligently. Pettis writes:

Capital inflows could be controlled through a number of mechanisms, including taxes, volume restrictions, bank reserve requirements, government approvals for transactions, and limitations on investor eligibility. An effective capital inflow regulation regime would need to be flexible, allowing for benign, temporary trade imbalances that balance an increase in productive investment while penalizing short-term and speculative inflows.

Ultimately, focusing on financial literacy operates as a diversion, individualizing risks that can realistically only be addressed by macroeconomic policy changes. Achieving a balanced, prosperous economy requires correcting the underlying structural imbalances: restoring labor’s share of income at home and abroad, curbing financial extraction, restoring the balance of savings and investment through effective trade and capital policies, and stabilizing the fiscal position. Only when policy addresses the structural drivers of financial insecurity and inequality (both internationally and domestically) will healthy savings become a natural consequence of economic participation.

- China’s savings rate is taken from Zhang, et. al. The remaining figures are from worldpopulationreview.com. ↩︎

- Readers may be more familiar with the terms “trade deficit” or “trade surplus,” which are simply two manifestations of the status of the current account. ↩︎

- I highly recommend Trade Wars are Class Wars by Pettis and Matthew C. Klein for an extensive overview of global macroeconomics and its effects on domestic savings rates. ↩︎