How Earnings Provide a Stable Investment Perspective

Equity investing can be gut wrenching. Looking at the exchange value of your investment during a market panic or after a decade or more of lost returns is enough to challenge even the most dedicated investors. Karl Marx marveled at the way “fictitious capital” could bear almost no relationship to the intrinsic value of the underlying assets:

To the extent that the depreciation or increase in value of this paper is independent of the movement of value of the actual capital that it represents, the wealth of the nation is just as great before as after its depreciation or increase in value.

Karl Marx, Capital Vol. III

The implications of this lesson–that the underlying value of businesses themselves are what matters–can play an important role in the behavior of investors if they understand it correctly. Equity market valuation should ideally represent a discounted cash flow of income (either from dividends or capital appreciation). To that end, some investors might try to estimate the intrinsic value of their investments via a discounted cash flow model, but in practice, that isn’t very straightforward for an index like the S&P 500.

Instead, a fairly simple approach would be to estimate the annualized earnings produced by your investment. Because earnings are less volatile that equity valuations, and cyclical adjustments tend to smooth out returns even more, the estimated earnings income from your portfolio is pretty stable.

When the stock market declines in value, the cyclically adjusted earnings yield (CAEY) goes up, meaning expected returns also go up. The CAEY is the inverse of the CAPE ratio, which is a widely established indicator for market valuation. It is also a good estimate of future returns and the safe withdrawal rate.

For a dramatic example, the S&P 500 returned negative 42% between December 1999 and September 2002, but the CAEY went from a record low of 2.21% in December 1999 to a more historically average 4.75% in September 2002. If you had $1,000,000 dollars invested in the S&P in 1999, it would have delivered over $22,000 in earnings. By 2022, at the market low, your portfolio would have dropped to $575,365.30, but since the earnings yield increased, your portfolio would be delivering over $27,000 in earnings, for a total increase of over $5,000.

| Date | Portfolio Value | CAEY | Earnings Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12/31/1999 | $1,000,000 | 2.21% | $22,067.84 |

| 9/30/2002 | $575,365.30 | 4.75% | $27,354.01 |

Here is a chart of the “lost decade,” comparing the compounded growth of the S&P 500 vs. the compounded “earnings value” – the earnings generated by your investment. The earnings value had some volatility during the Great Recession, but otherwise it is a pretty smooth ride up (The units in the chart are a meaningless reference point to compare the growth of the investments against the earnings value from the same starting point).

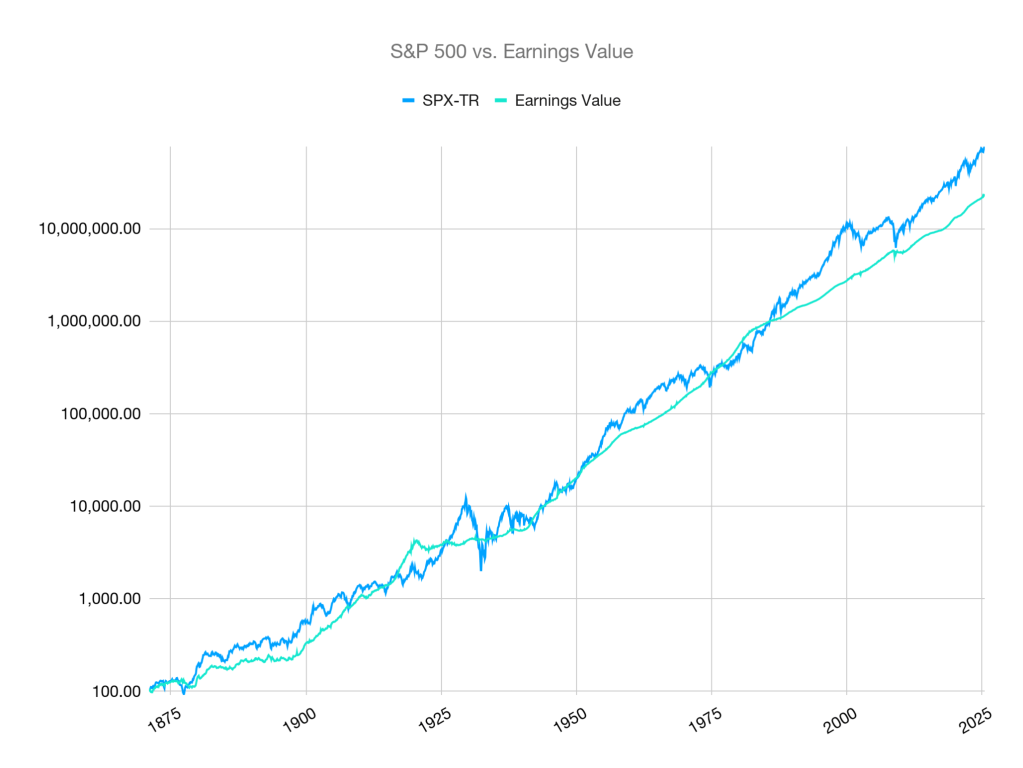

Going back further to 1861, we can see that earnings values have largely kept up with the growth of the S&P, although higher valuations have meant that the earnings have lagged more recently (chart in log scale):

Earnings from this perspective have been both far less volatile and fairly uncorrelated to the market itself. That makes sense because the CAEY is cyclically adjusted, which controls for volatility by averaging the inflation-adjusted earnings over the last ten years. Using standard deviation as a metric, the S&P 500’s annual volatility since 1861 has been roughly 16.5%, while the earnings’ volatility has been about 5%. The growth of the two have only been slightly correlated with a correlation coefficient of 0.11.

To put this in more concrete terms, the largest drop in the history of the S&P 500’s history would have cut your investment by about 84% during the Great Depression. However, your earnings value during this time would have only dropped by a little over 22%.1

By tracking your earnings value, you can both give yourself a better estimate of the real value of your assets and provide yourself a behavioral tool to help you stay the course. The easiest way to do this is to take your current asset value and multiply it by the current CAEY. My Asset Allocation Google Sheets tool includes a regularly updated estimate of the CAEY for the S&P 500.

If you own assets other than the S&P 500, you could use Research Affiliates’ Asset Allocation Interactive to find the expected return of your portfolio. RA’s tool is updated monthly, so it wouldn’t be difficult to get a fairly good picture of your portfolio’s intrinsic value on an ongoing basis.

Personally, I have been tracking my earnings value for the last year or two and it has drastically improved my understanding of market valuations and expected returns. Hope this insight can help you weather the storm during the next bear market.

- Actual earnings per share dropped by about 75% peak to trough during the Great Depression. During massive market dislocations, credit events and financial crises, the CAEY may undercount the impact to real earnings, especially at first. The cyclical adjustment process is meant to even out volatility, which is both its strength and its weakness. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.